In the Mid West, every winter farmers used to tie a rope from their back door to their barn. During blizzards, when there were no landmarks, no paths, no visibility, and no sound except the roar and howl of the storm, they clutched the rope to make their way out to the barn to feed their horses. Then they followed that lifeline back home.

I learned about the winter ropes from Parker Palmer whose wonderful book, A Hidden Wholeness, describes various practices for engaging the storms of life.

It’s been a stormy week. On Wednesday, as I was hefting a pot of chili off the stove to bring to a soup supper and concert, my phone buzzed. The county emergency services department had issued a flash flood advisory. We were cautioned to avoid travel.

Should I go out or should I stay home? On one hand, it would have been wonderful to sink into an armchair, toss a log onto the fire, and start reading the mystery that had just arrived in the mail. And I had a perfect excuse! My phone had buzzed. The county had spoken. I felt like a kid who’d gotten a note from my parents excusing an absence.

On the other hand, I’d signed up to bring soup. People were going to show up hungry, expecting supper. I wasn’t the only soup provider, but what if the other cooks stayed home too? Additionally, what about the local high school chamber choir, all 32 of them and their teacher. What if no one showed up for their Christmas concert?

The county-wide flash flood advisory did not really apply to my situation. Honestly, I knew that. The warnings pertained to steeper areas that had lost vegetation because of wildfires. Those areas were in danger of flash floods. My route was not. I could drive safely to church, on well paved back roads.

Reluctantly, I shrugged into my rain coat, hauled my pot of chili out into the storm, and drove slowly, watching for deep puddles.

To my surprise, the church basement was full. Everyone who’d signed up to make soup was there. And the salad and the bread makers showed up too. We had so much food the parents of the chamber singers could eat too.

After dinner we marched up the back stairs and packed into the pews. The young singers were brilliant, glowing, accomplished. For more than 20 years they’ve consistently won gold medals at national competitions, largely due to their teacher’s dedication and vision. Every one of the singers was there.

My take away is not that it is good to ignore travel advisories. Rather, my take away is that it is good to hold myself accountable, to exercise independent judgment and to take calculated risks.

The rain this week was a low-risk opportunity to test my rope. Connection and community led me out into the storm. Soup, song and gratitude nourished me on the way home.

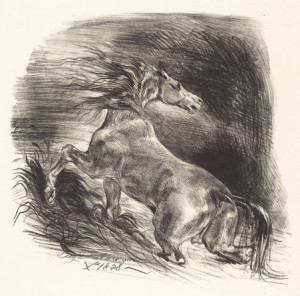

Delacroix, Wild Horse in A Storm, courtesy of the National Gallery of Art

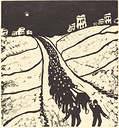

Legros, Man Watering A Horse, courtesy of National Gallery of Art

Last week I was anxious and sad. Although I kept going with ordinary life, I feared our old dog was dying. Mysterious yelps, sudden bulges, listlessness and clouded eyes reminded me of every dog I’ve had that died from cancer. I held off going to the vet, avoiding bad news. Finally when a tennis-ball-sized swelling appeared overnight, I took him in. The vet lanced the abscess, gave him antibiotics, and today he’s skittering around like a puppy.

Last week I was anxious and sad. Although I kept going with ordinary life, I feared our old dog was dying. Mysterious yelps, sudden bulges, listlessness and clouded eyes reminded me of every dog I’ve had that died from cancer. I held off going to the vet, avoiding bad news. Finally when a tennis-ball-sized swelling appeared overnight, I took him in. The vet lanced the abscess, gave him antibiotics, and today he’s skittering around like a puppy.

Recently I encountered Kate Munger at a conference. Kate founded the

Recently I encountered Kate Munger at a conference. Kate founded the