I tell folktales and myths at a residential program for women in substance abuse recovery. The women are there by court order and they also have open cases with Child Protective Services. As the seven of us sit in the somewhat shabby living room, we can usually hear toddlers and babies in the adjoining kitchen, which doubles as the child care room. Often one or more of the women is sick, suffering from dental problems (a common side effect of methamphetamine use) or medication issues (since many of the women have a dual diagnosis of a mental illness in conjunction with addictive issues) or just the garden variety ailments that crop up when people with young children live in close quarters. Nevertheless, the problems and pains recede as the story is told. The women relax. Their faces and bodies soften. Their hands unclench. They breathe more easily, often in unison. Officially, we call the sessions Narrative Studies, though the women just call them story sessions. They love them. As one woman said recently, “I can’t wait for story days. I always feel better about myself, more hopeful, more determined, than on regular days.” She articulated my deeply held conviction: stories can change lives.

I got into therapeutic storytelling by accident. A friend who worked at a domestic violence shelter was having trouble with her group. “They’re stuck,” she said, “and I don’t know what to do. Would you just come and tell a story?” I chose a traditional Scottish story, The Stolen Child, about a woman’s journey to recover her child from a dark underground kingdom. As soon as I finished, a woman burst out, “That dark king—he’s just like my ex!” Conversation bubbled up around the room as the women made connections to the story. “When she fell off the cliff, that was like me running away from home.” “I wonder what the stolen kid felt like, if he thought his mother had forgotten him.” “She was lucky, she found those gypsies to help her.” And so on, each one finding the moments in the story that spoke to her, that gave voice to her fears or articulated her deeply held desires. Hearing a story and making personal connections, finding personal meaning, is a powerful activity that allows us to arrive at new understandings of ourselves and our lives.

Recently I’ve settled on a basic structure for the story sessions. The first half is devoted to telling the story and facilitating a general discussion of the story. The last half is focused on a particular theme that can be found within the story, such as managing anger, transforming negative self talk, processing grief, improving self esteem, developing healthy relationships, dealing with anxiety, connecting to feelings, forgiving ourselves and others, or releasing shame. The balance between open-ended dialogue and specific focus lets the listeners make personal meaning but also keeps the sessions from becoming too repetitive. It also allows me to participate in the larger curriculum set by the hosting organization, while helping group members recognize and heal unhealthy patterns.

Working with stories in a group adds a collective dimension that enriches personal experience. For example, I often tell a Japanese myth about Amaterasu the Sun Goddess. There are many aspects to the story: Amaterasu’s flight from her violent brother, her anxious time of hiding in the cave, her restored sense of self upon seeing herself in a mirror, her brother’s ultimate redemption, etc. However, I use the story to work on issues related to depression. In the second half of the session, we focus on Amaterasu’s “cave experience.” We talk about what drove her into hiding and what helped her come out of hiding. We talk about our own “cave experiences,” and orally compose a group poem with the following stem lines: I went into hiding when….In the darkness, I felt…I knew I could come out when…Stepping into the light, I see…..Later I type up the poem and bring it back. It is always a proud moment for the group. Each group member recognizes her individual contributions, her own personal experiences, embedded within the whole poem. Seeing the whole poem helps make sense of experiences that heretofore might have felt fragmented, isolated, and overwhelming. Stories heal in part because they reassure us that experiences which seem purely personal are in fact part of collective human experience. Bluebeard shows us that sexual predators have always existed and could be survived with courage and assistance. Demeter shows us that humans have always lost loved ones and that grief has its seasons. Corn Mother shows us that sacrifice and hardship can lead to new life. When we access the wisdom of stories, we find a corresponding wisdom within. We recognize its truth immediately; it is part of our birthright as human beings.

At a county group for people with clinical depression and anxiety, I recently told an Inuit story, Skeleton Woman, about a young woman who was driven into the sea by polar bears and then drifted helplessly underwater as a skeleton before her healing process began. Her pain and difficulty are very fully depicted, as are her stages of recovery. It might seem that this story would be upsetting for people dealing with ongoing depression and anxiety; however, the story was well received. The group members knew what it was like to drift helplessly in the darkness, feeling powerless and alone. The story offered them a visual image and a metaphor to help describe prolonged depression, giving them a new way to comprehend and process that condition. Because the group members could identify deeply with Skeleton Woman’s struggles, they could also believe in her redemption, and cling to it as a beacon of hope for their own lives. In this way stories foster resilience, provide encouragement, and sustain us in very difficult times. I continue to volunteer in numerous therapeutic settings because it is privilege to witness the transformations possible through story. Over and again, I see a new light in people’s eyes, a rebirth of hope, an upsurge of courage and determination. Challenges that had felt overwhelming seem manageable. Like a rising moon, a story can provide light in the darkness.

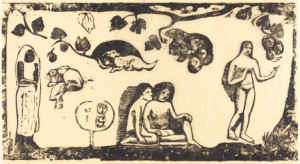

Women, Animals, and Foliage by Paul Gauguin, courtesy of the Getty Museum

Women, Animals, and Foliage by Paul Gauguin, courtesy of the Getty Museum